Game 71: Lynn Shackelford - Chinese Chicken Salad

In Wilt Chamberlain’s audacious autobiography Wilt, he recalls a moment while waiting for a delayed TWA flight that almost got him arrested. After making an off-hand joke to a TWA worker about packing a gun in his carry-on bag, Wilt writes that Chick Hearn’s “assistant” Lynn Shackelford came by to tell him that the FBI wanted a word with the big man. The word assistant here is key since the former UCLA great Shackelford was hired by Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke as more of a bodyman (and traveling secretary) than a traditional color commentator.

That was the case for most of Chick Hearn’s sidekicks during his enduring run as the Lakers’ play-by-play announcer from 1960-2002. To sit next to Chick was a privilege, but it was a silent one. Even if you had the balls to squeeze in a word, Chick would run you over with his patented stream of wordplay, an exhalation of the English language that explained the hardwood happenings in a simulcast to those tuning in on both TV and radio.

Starting with the 1966-1967 season, Chick had a revolving door of sidekicks who received a paycheck while learning the true meaning of only speaking when spoken to. From these ranks came a future Hall of Fame coach/executive and an eventual legendary sports broadcaster in his own right. Since these “assistants” couldn’t speak for themselves, I’ll do the talking for them.

——————————

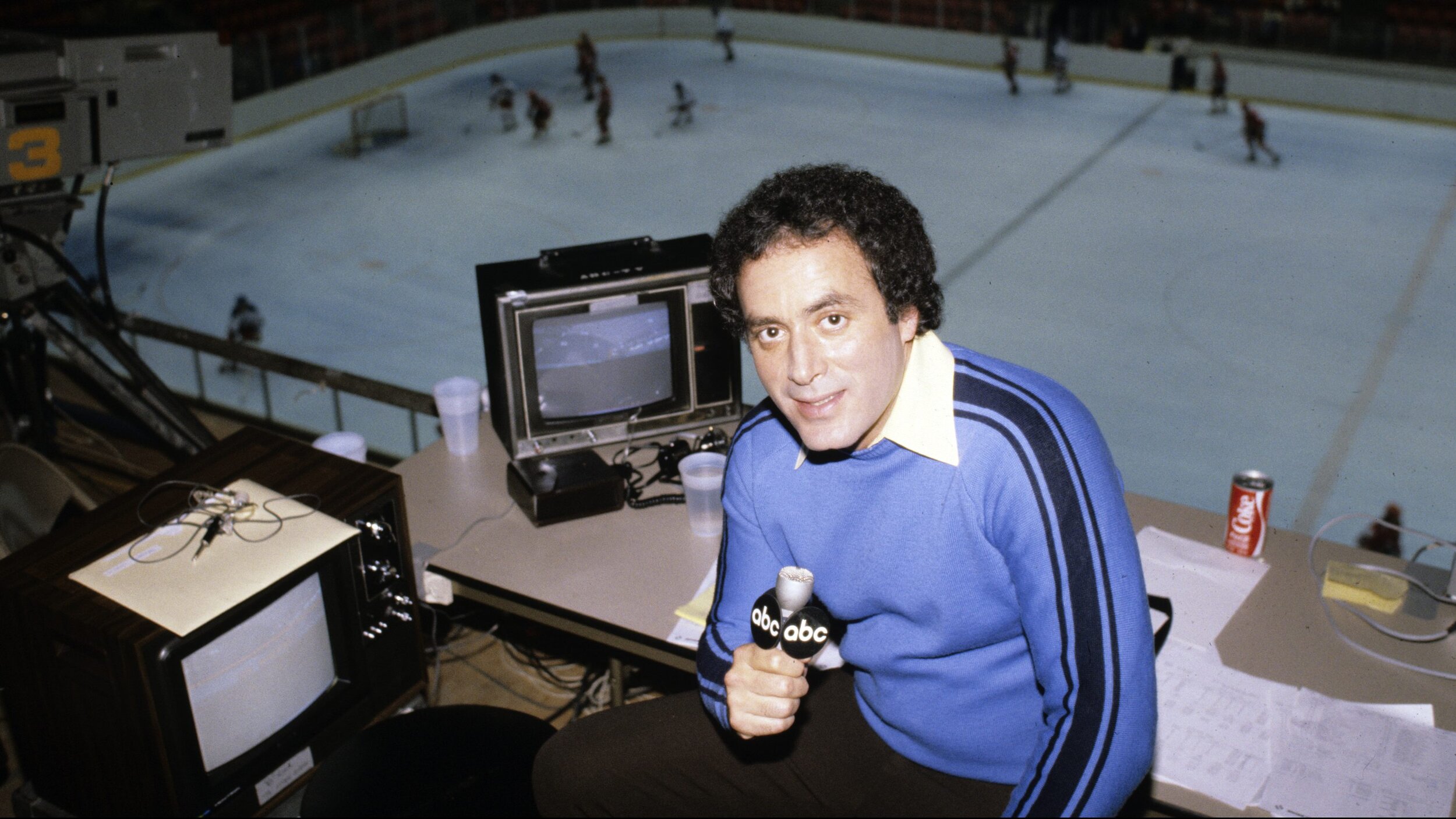

AL MICHAELS

For his first five seasons, Chick Hearn worked alone. He didn’t need a sidekick, a former jock who needed a job, to explain the play that just occurred. Chick would do it himself, seamlessly transitioning from play-by-play to commentary and back, while inventing new phrases like slam dunk, alley oop, and pretty much every basketball term you thought was invented well before the Lakers moved to Los Angeles.

But a year after buying the Lakers and Kings, owner Jack Kent Cooke wanted to shake up the broadcast. So he brought on board a 22 year old Al Michaels as Chick’s sidekick. Today, Michaels is regarded as one of the greatest sports broadcasters to ever speak into a microphone. It’s his iconic voice that can be heard yelling “Do you believe in miracles? Yes!” when the United States upset Russian in the 1980 Winter Olympics and calmly stating “I’ll tell you what, we’re having an earthq--” as the Bay Area was rocked by a 6.9 earthquake during game 3 of the 1989 World Series. It’s Michaels who’s been the voice of ABC’s Monday Night Football and its cultural successor, NBC’s Sunday Night Football, for over three decades. And it was Chick Hearn’s first sidekick who, in 2004, became the first broadcaster to have called the Super Bowl, World Series, Stanley Cup Finals, and NBA Finals over the course of his career.

But back in 1966, Michaels was just a “sacrificial lamb.” He was hired over Chick’s objections and fired two weeks into the gig.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Michaels grew up listening to radio broadcasts of the Yankees, Dodgers, and Giants during the golden age of New York City baseball. As a child, he was introduced to the business side of sports by his father, Jay, who led the MCA talent agency’s sports division. By the time he reached his teens, a passion for sports broadcasting was distilled into his very being. After graduating from Arizona State as the campus broadcaster, Michaels moved to L.A. and PA’d on The Dating Game. He was soon promoted to talent coordinator where he was in charge of picking the show’s women contestants. I don’t blame if you just imagined Michael’s unmistakable voice, kind of like if Kermit the Frog was from Brooklyn but tried to speak in a Mid-Atlantic accent, flirting with potential guests in between drags of his morning’s 8th cigarette.

In 1966, Kings and Lakers VP Alan Rothenberg received an audition tape from Michaels. He loved it, calling Michaels a “mini Vin Scully,” and pitched him as Hearn’s sideman. Chick hated the idea… which was exactly the point. Rothenberg and Cooke knew the idea would take some getting used to from Chick, so they offered up Michaels to the lions. He was fired four games into the regular season without speaking a single word as a color commentator. Instead, Michaels was banished to halftime where he did scoring reports. Then one night at an airport, Hearn gave Rothenberg an ultimate: "If the kid gets on the plane, I ain't."

Don’t feel too bad for him. While Michaels was in the midst of a months-long depression, his father-in-law invited him on a business trip to Hawaii. There, Michaels quickly found a new job calling games for the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League. Within 5 years, Michaels became the voice of the Cincinnati Reds and was hired by NBC to call the World Series after the Reds won the pennant. Once Michaels was far enough removed from his inglorious exit, he forgave Chick for his mistreatment and the two became close friends. But more importantly, Michaels realized the real reason he was fired:

““Cooke wanted to bring in Hot Rod Hundley to work with Chick, and he needed a buffer so Chick would get used to the idea. And that was me.” - Al Michaels”

HOT ROD HUNDLEY

Jerry West is synonymous with West Virginia basketball, but he wasn’t the first Mountaineer to play for the Lakers. That would be Hot Rod Hundley, a 2x NBA All-Star who would go on to become the voice of the Utah Jazz for 35 years. But before he became a beloved figure in Mormon Country, Hundley got his nickname for the flashy ball-handling he displayed on the West Virginia court. Take a look at these fake passes and no-look passes in the video below. Hundley’s documentary says he could’ve been a Globetrotter, but he’s more like a precursor to Jason “White Chocolate”Williams. These passes weren’t designed to make the crowd laugh, they were intended to humiliate the opposing defender.

In the 1957 NBA Draft, the Cincinnati Royals drafted Hundley first overall and sent him to the Lakers, where he would spend his entire abbreviated career. In 1960, the Lakers moved to L.A. and Hundley teamed up with that year’s #1 overall pick, fellow West Virginia Mountaineer Jerry West. While bad knees ended Hudley’s career just as West’s began to take off in 1963, the two were always linked by their genesis from the most unlikely of pools. When the duo played a charity game at the WVU Coliseum decades after their college careers were over, Hundley was said to have told West that he built this building. West answered back with “Yeah but I paid it off.”

In the ‘60s, Hundley gained a reputation for drinking and womanizing and subsequently abandoned his family, a little-known part of his history that was shared by his children in the 2018 documentary Hot Rod. But to Jack Kent Cooke, he was the perfect color commentator: A charming former jock with the gift for gab. After Al Michaels was removed, Cooke’s real first choice was an easier sell to Chick. “At least he won’t be as bad as Michaels” was probably Chick’s first thought.

After two seasons with the Lakers and five with the Phoenix Suns, plus some national work for CBS, Hundley was hired by the expansion New Orleans Jazz in 1974 as their play-by-play announcer. And that’s where he stayed for 35 years, doing the radio and TV simulcast just like Chick. In 2006, he was bumped off the TV broadcast to make way for his successor Craig Bolerjack. Or maybe it was because of his appearance in 2006’s Mormon basketball comedy Church Ball starring Gary Coleman, Clint Howard, and the least famous Wilson sibling, Andrew Wilson.

In 2009, the 74 year old decided to retire from the Jazz but the broadcaster had a few games left in him. When both Lakers color commentators for TV and radio, Stu Lantz and Mychal Thompson, had to miss games for personal reasons, Hundley and a still-playing (but injured) Luke Walton filled in behind the mic. In a perfect bookend to his career, Hundley called six games for the team that started his career over a half century earlier, the same franchise he jolted from when it became clear he would never get an on-air word in. Hundley died in 2015 at the age of 80 from Alzheimer’s Disease.

LYNN SHACKELFORD

Unlike Al Michaels or Hot Rod Hundley, Lynn Shackelford had no dreams of branching out on his own as a lead play-by-play announcer. He was the first of Chick’s sidekicks to fully understand his role. And because he “didn’t have anything going” on his professional life, he was more than happy to sit down and collect a check.

An L.A. native, Shackelford starred at John Burroughs High School in Burbank before deciding to attend the budding basketball dynasty at UCLA in 1965. There the 6’5” forward with a left-handed shot that John Wooden described as “beautiful” became one of only four players in history to start on three national championship teams. Not to take away anything from Shackelford, but the reason he’s on that list is solely due to one of his teammates: Lew Alcindor, the future Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. It was the transcendent and dominant Alcindor who made his name leading the Brubabe freshman team -- freshman and varsity teams were separate until 1972 -- in a shocking 15 point defeat of Wooden’s varsity team in 1965. Basketball was never the same after that. The NCAA even banned the dunk to try and stop Kareem.

After Shackelford was promptly cut weeks after being drafted by the Houston Rockets in the 6th round of the 1969 NBA Draft, he found himself playing for the ABA’s Miami Floridians. 22 games later, he was cut again and faced with diminishing basketball prospects. But back in L.A., Hot Rod Hundley was tired of playing second fiddle and left for a job in Phoenix. So that empty seat was filled by Shackelford. With Chick’s approval, of course.

By Shackelford’s telling, he got along fine with Chick on a personal level. “Off the air, we got along very well,” he told the L.A. Times in 2009. “We sat together on planes and I enjoyed his companionship very much. He was much more relaxed.” But when the mics were on, the indignity of his assignment would gnaw at him. During gametime, Chick was a “perfectionist” who was “not easy to work with.” Sometimes Shackelford would sit there and wonder what he was even doing in that seat

Shackelford’s on-air muzzling wasn’t the only embarrassing part of his job. Shackelford also served as the team’s traveling secretary during a time when it was common for those duties to be given to a trainer or other employee. This meant he had to schedule airline flights and bus pick-ups, reimburse petty cash, and repeatedly call grown men sleeping in their hotel rooms to wake up for the bus they were about to miss.

In 1977, Shackelford unshackled himself by moving onto KCAL 9 to work as a studio analyst for the longtime home of the Lakers. His replacement was a former bench player for the Lakers’ 1971-1972 championship team that rattled off a still record 33 games. But that man, Pat Riley, only lasted 2 ½ seasons before a chain of violent events landed him in a position to become a basketball immortal.

PAT RILEY

It’s hard to imagine Pat Riley playing second fiddle to anyone. The style icon has spent the last four decades building championship teams in South Beach and coaching decade-defining teams in Los Angeles. But in 1970, Riley had his floundering NBA career saved by none other than Chick Hearn. It wasn’t the only time in the ‘70s that Hearn tossed Riley a life preserver.

In college, Riley was a star multi-sport athlete at the University of Kentucky in football and basketball. As an undersized forward, he was the leader of the 1965-1966 Wildcats, a team best known for losing in the NCAA title game to Texas Western, the first championship team to start five black players. But after being drafted 7th overall by the San Diego Rockets in the 1967 NBA Draft, he instantly fell out of favor with the man who drafted him, coach Jack McMahon. They moved the 6’4” Riley to guard, a position he had never played before. According to Jeff Pearlman’s Showtime, McMahon quickly pulled him aside and told him “that was the worst five minutes of basketball I’ve ever seen.”

After three mediocre years in San Diego, Riley was picked up by the Portland Trailblazers in their expansion draft. He was cut before the season began and his prospects for suiting up in the NBA looked bleak. But then fate intervened. As he and his wife walked out of the arena the night he lost his job, he crossed paths with Chick Hearn. Hearn wasn’t just the Lakers’ longtime broadcaster; he also served as assistant general manager for most of the 1970s. He offered the dejected player some words of encouragement and then convinced Jack Kent Cooke to sign Riley a couple days later. Riley spent five years on the Lakers in a clearly defined role according to Showtime: His job was to “play scrappy defense and, during practice, make Jerry West’s life a living hell.”

Riley won a championship during his stint on the Lakers, but after a season in Phoenix, he was once again lost. Without basketball, Riley had no guiding star to tell him how to live his life. He and his wife would hang out at the beach all day playing volleyball, hoping that the answering machine back home would hold a message of restoration. Of reinvention. Of anything! He just needed a job. Then one day, it did. Lynn Shackleford had left the Lakers to work for KCAL 9 and Chick Hearn wanted to know if Riley wanted to fill his spot.

Riley only spent 2 ½ seasons behind the mic before a series of violent events -- the unsolved murder of Jerry Tarkanian’s best friend and Jack McKinney’s near-fatal bicycle accident -- pushed Riley into the role of assistant coach. But Riley looks back on those years as his crash course on how to become a professional leader of men. When McKinney was let go and Paul Westhead asked Riley to join his staff, it was Hearn who pushed him to take on the new challenge. And when Westhead was pushed out by Magic Johnson and Riley took over, he based his coaching style not on his Hall of Fame coach at Kentucky, Adolph Rupp, but on Hearn. It was Hearn’s meticulous preparation before a game -- notecards and memorized statistics and imaginary play calls and interviews -- that Riley absorbed and translated to his new job.

KEITH ERICKSON

Keith Erickson, a standout championship forward at UCLA who later won an NBA title as part of the 1971-1972 Lakers, worked as Chick Hearn’s color commentator for seven seasons. He resigned following the 1987 playoffs to work full time at Sports Fantasies, a company that produced personalized game tapes of famous sports broadcasters... like Chick Hearn and Keith Erickson. Was it your dad’s dream to hear his name roll off Chick Hearn’s tongue after Dad passed to Kareem for a game-winning skyhook? Apparently in the 1980s, it was profitable enough for Erickson to leave the Lakers for this gig.

For more on Keith Erickson, check out Game 25 of Goldstein and Gasol. In that post, I examine the accidental overdose death of his daughter Angelica and the L.A. Times’ decision to print Letters to the Editor that amounted to nothing more than hateful proto-message board comments.

STU LANTZ

After Keith Erickson's resignation, the team used the Summer League to audition Stu Lantz, a former NBA player who ended his eight year career in 1976 following a couple seasons with the Lakers. After only two weeks, the Lakers made their decision. And thus, Chic N’ Stu, the longest Lakers broadcast partnership, was born.

Unlike his predecessors, Lantz wasn’t a nervous 22 year old kid or an announcer with higher ambitions or someone equally in awe and afraid of the legendary announcer. Hot Rod Hundley once told Sports Illustrated "You can say, 'That's right, Chick,' as many times as you want. But if you say, 'That's wrong. Chick,' you're gone." But Lantz wasn’t afraid to correct Chick if he got something wrong, a more common occurrence as the Hall of Famer broadcasted into his 70s and 80s. That likely earned Chick’s deep respect, the kind that is doled out very rarely by a man used to people treating him like royalty. In an L.A. Times piece that came out just weeks before Chick’s death, their 15 year relationship was described in patriarchal terms. “No one called more. And we still talk on the phone all the time” is how Chick looked back on his mid-season recovery from heart surgery in 2001. That surgery was what ended his decades-long streak of calling Laker games. He returned to call the Lakers’ 3-peat championship in June 2002 and the ensuing parade. But just two months later, he died after falling in his backyard.

But who is Stu Lantz? He sat next to Chick Hearn for the final 15 years of his career and has stayed in the same spot with Chick’s successors Paul Sunderland, Joel Myers, and Bill MacDonald. And yet, Angelenos know very little about a man who could top Chick’s years of service by the time he hangs up his mic.

Lantz was born in 1946 in Uniontown, PA where he grew into a star football and basketball player for Uniontown Area High School. He was drafted by the San Diego Rockets in 1968 and had an unspectacular career that was ended by a back injury, but he’s stayed in California’s most southern city ever since. For 34 seasons, Stu has made the 3 hour drive from his home in San Diego to The Forum and Staples Center. Stu says the trip takes him 1:45, but that’s horse shit, even factoring in that he probably lives in one of the city’s northern suburbs.

Lantz spent a few seasons working for the San Diego Clippers and CBS’ college basketball broadcasts, but when Erickson’s position became available, he was the first person they called. Even in his first season, Lantz was getting rave reviews for being the first Lakers color commentator to have no qualms about questioning Chick Hearn on the air. When we think of Lakers and longevity, we think of Chick and Jerry West and Kareem, basketball lifers indelibly linked to the league’s most iconic franchise. But for the last 33 years -- from the Lakers’ back-to-back titles in 1987/1988 to the plane ride where the 2019-2020 Lakers found out about Kobe Bryant’s death -- Stu Lantz has been there too, taking us to a commercial break with his smooth baritone voice.

————————

Chinese Chicken Salad

2 cups Chinese rice vermicelli, deep fried until puffy

½ pound chicken breast, cooked and shredded

1 small head iceberg lettuce, shredded

6 green onions, shredded

2 tablespoons toasted sesame seeds

2 tablespoons chopped macadamias

Coriander

Dressing: 1 teaspoon salt

6 tablespoons vinegar

½ cup cup salad oil

1 teaspoon pepper

4 tablespoons sugar

Place salad ingredients into a bowl and mix. In a separate bowl, mix dressing ingredients and then toss with salad.

First things first: My quarantine substitutions. There were no macadamias at the store so I used leftover almonds (themselves a substitution for walnuts) from Frank Robinson’s chicken and walnuts recipe. Albertsons was also out of green onions. I would’ve grabbed some from the Thai market but this is the week (mid-April) we’re supposed to avoid trips, even to the market, unless absolutely necessary. I love green onions but not enough to risk undergoing intubation.

This recipe is your typical Chinese chicken salad which is… not a favorite of mine, to put it nicely. I love Americanized Chinese food. One of these days when the quarantine is lifted and I get a new car -- my 2004 Hyundai Sonata needs a rebuilt engine and it honestly couldn’t have come at a better time -- I’ll trek out to the San Gabriel Valley to gorge myself at the California Mecca of authentic Chinese food. But for now, I’ll have to stick with stuff created here in the good ol’ U.S. of A. Like Chinese chicken salad, which is rumored to have been invented in the 1960s by Madame Wu of Madame Wu’s Garden in Santa Monica.

I’ve never been a fan. Iceberg lettuce and oranges and crunchy items all topped in a sickly-sweet sauce? American salads have come a long way since those days. I’m spoiled by perfectly ratio’d Mendocino Farms salads teeming with fresh California produce and cage-free chicken. And then there are more authentic Asian salads like green papaya salads, known as som tam at Thai restaurants, that are bursting with flavor and heat and, most importantly, freshness. Sorry, Lynn. Sorry, Madame Wu. Sorry, line cooks at The Cheesecake Factory.