Game 44: Wilt Chamberlain - Shrimp Curry

Shortly after the Staples Center’s 1999 christening by Bruce Springsteen and the newly-reunited E Street Band, my dad took me to the shiny purple and grey spaceship jutting east of the 110 to see our first game at the new arena. It wasn’t the Lakers, Kings, or even the Clippers. Instead, he took me to one of sport’s most unique events: A Harlem Globetrotters game. Since 1926, the Globetrotters have put on more than 26,000 exhibition games showcasing a theatrical combination of athletic basketball ability and expert comedic timing. If you ever have a chance to see a Globetrotters game, do it. It’s like Cirque du Soleil meets Venice Beach streetballers who were on a UCB Harold team and had some nice bookings a few years back but now their manager can’t even get them in the room for a digital commercial audition and they’re thinking of asking the AD if they can teach more 101 classes but they feel guilty about perpetuating the UCB’s “business” model firsthand.

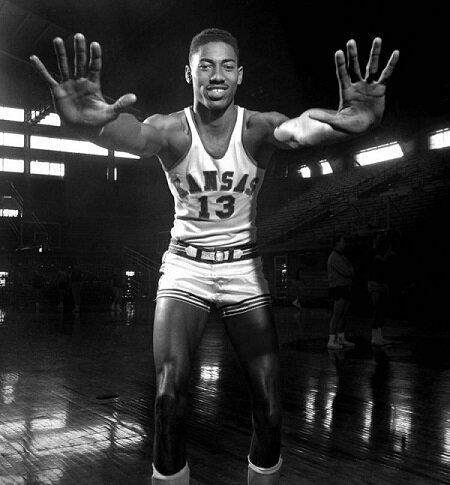

Not too many people know this, but Hall of Famer Laker center Wilt Chamberlain began his professional career as a Globetrotter. The Philly native was 6 feet tall by the age of ten and he started appearing on the NBA’s radar as a 6’11” high schooler. While he was still in school, Boston Celtics coach Red Auerbach had him play 1-on-1 vs B.H. Born, the University of Kansas Jayhawk who won the 1953 NCAA Finals Most Outstanding Player award. According to Wilt: Larger Than Life, Chamberlain crushed him so badly (25-10) that Born gave up on his dreams to play in the NBA and devoted his life to selling tractors.

The Big Dipper, as he preferred to be called compared to his other nicknames Goliath and Wilt the Stilt, attended Kansas where he continued his excellence as one of the nation’s best college players, not just in basketball but as a freak track & field athlete. The now-7’1” 275lb Chamberlain ran a 10.9 second 100 yard dash and excelled in shot putting, the triple jump, and the high jump. On the court, not only did he showcase razzle-dazzle skills like his finger roll and bank shot but also his unusual quickness and passing ability for a big man that preceded Giannis Antetokounmpo and Anthony Davis by 60 years.

He wasn’t long, at least metaphorically, for the college game. In his sophomore year, the Jayhawks made the 1957 NCAA Tournament and were slotted in the Midwest region to play their games in segregated Dallas, TX. There he was faced with vicious racism, enduring debris and spit and racial epithets while leading the Jayhawks to the title game. Their opponents, the UNC Tar Heels, pulled out a close victory by triple teaming Chamberlain, a tactic he would see used on him nonstop in his junior year. Frustrated with the NBA’s rules that barred him from playing until he finished his senior year, Chamberlain dropped out of Kansas. And in a move that preceded The Players’ Tribune by 60 years, he sold a story to Look magazine for $10,000 called “Why I Am Leaving College.” At the time, the best NBA players made about $9,000 in a season. Shortly thereafter, Chamberlain signed a $50,000 contract to barnstorm with the Harlem Globetrotters.

Chamberlain only played one year with the Globetrotters before his 14 year NBA career that saw him win two championships, 4 MVP awards, 7 scoring titles, 11 rebounding titles, and even an assist title -- the only center to ever lead the league in assists! But it’s notable for being one of the earliest cases in which a star athlete took on the crooked tandem of the NCAA and pre-free agency professional sports. Chamberlain knew his worth. And he knew how valuable he was to teams on and off the court.It was Chamberlain, ironically a proud Republican, who inspired star players to stand up against owners and demand a salary that was commensurate with the money they brought into the team via tickets, concession and merchandise sales, and later on, massive TV deals.

From Oscar Robertson’s landmark 1970 antitrust suit Robertson v. National Basketball Ass'n to modern superstars like LeBron James, who usurp owners to create their own superteams while getting paid nine-figure contracts, it all comes back to Wilt. It was the biggest, most charismatic, and strongest -- he could literally pick up opposing centers like a teacup -- player who laid the groundwork of not bending to the rich white men writing the checks and the rules. Of course it was Wilt. Even though he hated this particular nickname, he said it best:

““The world is made up of Davids and I am Goliath.” - Wilt Chamberlain”

——————————————

Shrimp Curry

1 pound shrimp, peeled and deveined

2 tablespoons oil

1 tablespoon coconut cream

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 teaspoon cumin powder

1 tablespoon powdered coriander seeds

2 medium onions, finely sliced

2 large tomatoes, chopped

Juice of ½ lemon

½ teaspoon turmeric

Salt to taste

Heat oil in a large saucepan and fry garlic and onions until soft, but brown. Add turmeric, coriander, and cumin and cook 1 to 2 minutes. Add some water if necessary to prevent from sticking. Add tomatoes, coconut cream, and about 1 cup of water. Simmer gently until sauce is thick, about 20 minutes

Add shrimp and lemon juice and cook for 5 minutes longer. Serve with rice and slices of lemon, in empty coconut shells.

My first curry. I’m not the biggest curry fan. It’s not that I dislike it, but if I’m at an Indian or Thai restaurant, I’m thinking about 15 other options before I even look at the curry. Still, I wanted to see what The Big Dipper cooked up.

It’s not as complicated as it seems. I picked up some big juicy raw shrimp from the Los Feliz Albertsons and had this whipped up in about 30 minutes. Did it taste good? Not really. But then again, I don’t really like curry that much. So what the fuck do I know?